Eeuwig moment / Everlasting moment

Publisher: Steven Hond / uitgeverij Komma

Design: Karin van Iterson

Text: Bertus Pieters

ISBN: 978-90-831429-7-5

Made possible by Jan van Hoof gallery 's-Hertogenbosch

Sold out

Heading for the absurd carrying a handbag

Bertus Pieters, July 2021

Jenny Ymker is a photo artist. Sure, the most monumental and maybe most conspicuous part of her current work are her Gobelins, tapestries. Yet it is obvious even to the untrained eye that the images of the Gobelins were originally photos. Thanks to the monumentality of the tapestries and the fact that they do not have skimming light like a printed photo or a painting, and because the colours are so absorbing, there is a minimal barrier between the image and the viewer. Viewers can fully immerse themselves in the composition, both in the image itself and in its details, which cause the whole to dissolve into pointillistic splashes of colour. This is what textile is capable of, but it is supplied and made possible by the photographic image. This is not altered by the fact that instead of being printed on paper or made visible through projection, the photo has been translated into yarn. Indeed, it adds something. Tapestries used to be highly valued decorations depicting important historic, mythological or Biblical figures. In those times, too, tapestries enabled viewers to identify with the image, almost enter into it, without being hindered by a hard wall or the shiny surface of a skin of paint. Textile adds depth to an image, all the more so in the case of Ymker’s Gobelins. It is not just the perspectival depth that counts, but also and especially the depth of the material itself. The fibrous structure of the yarn give the colours their own depth, and there is no clear-cut boundary between the space in which the viewer stands and the surface of the tapestry. This also gives the colours their absorbing power and makes them so attractive to the viewer.

Technically, the Gobelins may be the most conspicuous works in Ymker’s oeuvre, but from 2019 onward she has also made a large number of photos in light boxes. The subject matter is the same, but their colours make it impossible to translate them into tapestries. The light box turns out to be just as wonderful a medium to show Ymker’s images as the Gobelins are. Again, they have no annoying skimming light, as the light shines through the photos themselves, lending the image an unparalleled brightness and pulling the viewer into the image. In line with these are the so-called ‘music boxes’, light boxes with a slowly moving image and with the sound of a soft, distorted music box melody added to it.

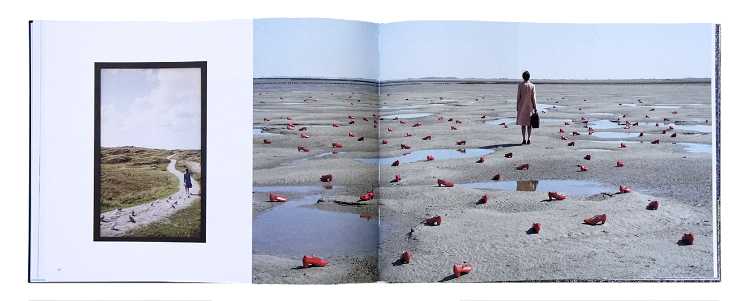

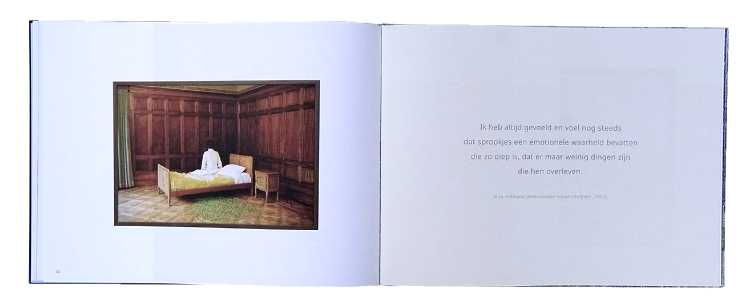

Besides photography, Ymker’s work is grounded in performance art. This is still clearly visible in early works from around the year 2000, in which the protagonist is an instrument of expression, as in a performance. In comparison a number of photos, created only a few years after a residency in Sweden, are much less ‘noisy’. In the Swedish photos the protagonist acts as a figure who sees herself in a dream, or as a vision in a daydream. The protagonist is no longer an instrument, but has become autonomous. The scenes are quieter, and this stillness is achieved by the protagonist. Besides that, the images are fairytale-like in atmosphere. This fairytale-like quality will return frequently in her later work; sometimes quite literally as in the light boxes The Red Shoes (2020), Gretel (2020) or Sleepless (2020), which contains a reference to The Princess and the Pea. There are also less direct references on images that suggest a fairytale-like content, for instance in various Gobelins featuring scenes with flowers, such as Blanket of Flowers (2016), Ophelia (2019) or Looking for Daisies (2020).

Let’s return to the Swedish photos for a moment, as they already seem to contain so much that would define her current work. There is a photo Woman in a White Dress (2002), in which a figure is looking out over the sea from a rocky shore. This is vaguely reminiscent of the photo Farewell to Faraway Friends (1971), an emphatically romantic piece by Bas Jan Ader (1942-1975)1, coincidentally also made in Sweden. Looking out over the water has acquired an emotionally charged meaning, especially since the work of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) – for instance in Mönch am Meer(1809)2. It may signify looking out to the future, the unknown, a longing for other, maybe purer worlds, the immersion into greatness an, as with Ader, a longing for the unattainable. In the end, it is the vast body of water opposite the earthly land to which man is bound both materially and physically, that makes the scenes into what they are, whether it concerns the aforementioned photos by Ymker and Ader or Friedrich’s painting. Later, the sea will return in Ymker’s Gobelins Winterreise (2015) and Le temps qui attend (2020). It seems that man’s loneliness in the big world, so clearly visible in the Swedish photos, forms a basis for Ymker’s more recent work.

Loneliness in a bigger world has remained a theme in Ymker’s work, but her preoccupation with the sublime – the overwhelming quality of the world – of Romanticism has made way for something else. In her work, it is not the almost pathological longing for unification with the greatness of the world that is important – so religious in Friedrich’s work and so fateful in Ader’s – but the constant dialogue between lonely man and the world that surrounds him. In this, Ymker is more akin to absurdism. Absurdity is part of everyday life, and the opposition between on the one hand individual man, with his aspirations regarding the world and the way he approaches it, and on the other hand the world that has little to no consideration for this. The tension in this contrast takes man’s efforts into the realm of the absurd. In his essay on the absurd, The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus was quite clear about this: ‘The world in itself is not reasonable, that is all one can say about it. What is absurd, however, is the confrontation with this irrational and desperate longing for clarity, whose call resounds in man’s deepest inner self. The absurd depends both on man and the world.’3 So the absurd requires two entities: the world and the individual human being, and both are always present in Ymker’s work.

The sense of the everyday absurd, the idea of the individual human being who over and over again is confronted with the world as with a machine that does not let itself be controlled, was present in Ymker’s work at an early stage, but only manifests itself in earnest around 2013. The greatness and the sublime of the world and the atmosphere transforms into an environment stretching itself silently around the protagonist – who is always Ymker herself. A world that sometimes yields, seems eager to communicate, while at other times unrelentingly determining the individual’s fate, but in the end always remaining silent and never willing to extend a helping hand. The sea, once so mysterious in Woman in a White Dress, in Sea Longing (2014) has been reduced to a large wall decoration, which does not mean, however, that its role has been played out. In Winterreise (2015) the spirit of the sublime may still be traceable – maybe through the reference in the title to Schubert’s Romantic masterpiece – but the figure with suitcase in hand has not lifted itself above the sea, maybe travelling in spirit rather than in person. To the sea it makes no difference, it just flows around the elevation on which the figure stands.

While in Woman in a White Dress an effort is still made by the figure to blend into the sublime world of the coastline, this opportunity is lost in later works. In the large tapestry Le temps qui attend (2020) the horizon is vast and the otherwise calm sea fans out across the silts in which a bench stands on which a figure is seated, seen from behind. The concept of this ‘Rückenfigur’ can (again) be traced back to Caspar David Friedrich, in whose paintings a lonely figure, seen from behind, has two functions: clarification of the perspective and the proportions in the image, and giving the viewer a person to identify with and experience what that figure experiences. In turn, this concept is derived from Romanticism. However, a significant difference is that in Friedrich’s case the Rückenfigur leads the viewer to experience the sublime of the whole, while in Ymker’s Le temps qui attend the Rückenfigur, sitting on the white bench her bright blue coat and handbag, is there in spite of the sublime and if anything, detracts the viewer from it. The Gobelin is considerable in size and the vast emptiness of the sea undeniably provides the biggest sensation. However, this sensation is immediately refuted by the blue of the figure on the white bench. In her loneliness there is no-one who will urge her to return home. She is sitting here vulnerably and left to her own devices, but also sovereignly in the apparent innocence of het bright-blue coat and her belongings in her handbag.

This is how protagonists in Ymker’s scenes often fare. Sometimes wondrous things happen, at times even emphatically, as in fairytales. This is true for the flowers in aforementioned works, but also for the blue thread held by the protagonist to negotiate an immense, snow-covered stubble field in the large Gobelin Landscape in White (2020). It is as if the flowers, this blue thread and other props in the images mediate between the two actors in the photos: the person and the irreconcilable landscape surrounding her. These props emphasize the absurdity of the contrast between both actors, but also help the protagonist to break through the absurdity over and over again.

This also makes the so-called ‘music boxes’(from 2019 onward), the boxes with moving images, an exciting development, for here the props have been limited to a minimum: the protagonist’s attire and a handbag. The faltering tinkle of the music box emphasizes the alienation cause by the clash between the woman with her handbag and the world, but also seems to be the basis from which – again – she goes forward in the world, confronting the absurd. She has also made a considerable journey: from expression via the sublime to the silent era of he absurd. The women in Ymker’s works may seem to have lost their way in an unforgiving environment, but with their imaginative power they find a way to turn loneliness into strength.

notes:

1 Bas Jan Ader, Farewell to Faraway Friends, colour photo, 48.5x57.5 cm, edition of three

2 Caspar David Friedrich, Mönch am Meer (Mok by the Sea), oil on canvas, 110x171.5 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

3 Albert Camus, Le mythe de Sisyphe; Essay sur l’absurde. Paris, Gallimard, p.38. English translation: The Myth of Sisyphus. London, Penguin, 2005.